An international team of more than 200 astronomers from 18 countries has published the first phase of the survey at unprecedented sensitivity using the Low Frequency Array (LOFAR) telescope.

Radio astronomy reveals processes in the Universe that we cannot see with optical instruments. In this first part of the sky survey, LOFAR observed a quarter of the northern hemisphere at low radio frequencies. Today (19th February 2019), around ten percent of that data is being made public. It maps three hundred thousand sources, almost all of which are galaxies in the distant Universe; their radio signals have travelled billions of light years before reaching Earth.

Black holes

Huub Röttgering, Leiden University (The Netherlands) says: “If we take a radio telescope and we look up at the sky, we see mainly emission from the immediate environment of massive black holes. With LOFAR we hope to answer the fascinating question: where do those black holes come from?"

Philip Best, University of Edinburgh (UK), adds: “What we do know is that black holes are pretty messy eaters. When gas falls onto them they emit jets of material that can be seen at radio wavelengths. LOFAR has a remarkable sensitivity which allows us to study black holes even in galaxies which only have jets on very small scales. We have discovered that these jets are present in all of the most massive galaxies, which means that their black holes never stop eating." The energy output in these radio jets plays a crucial role in controlling the conversion of gas into stars in their surrounding galaxies.

Clusters of galaxies

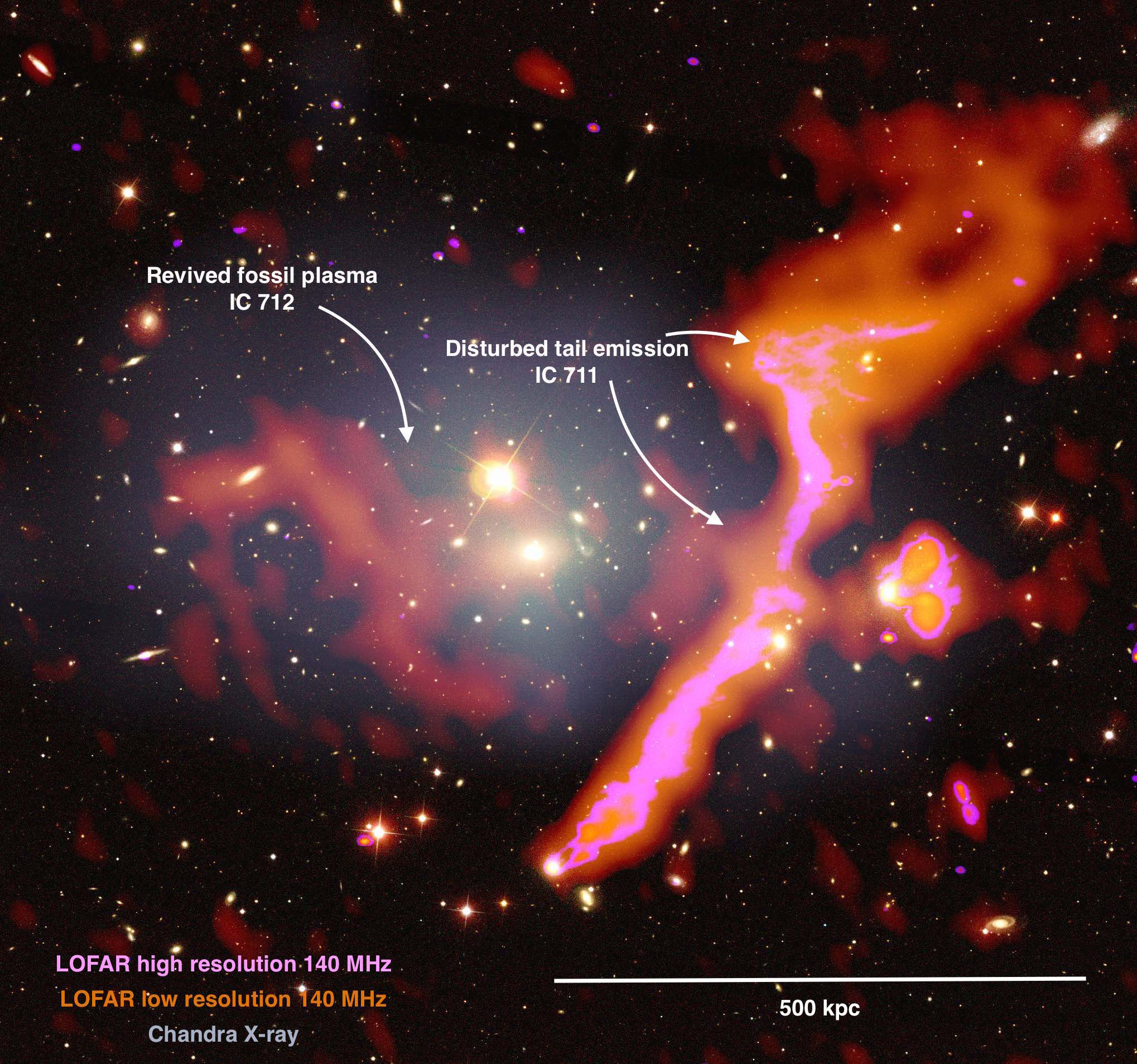

Clusters of galaxies are ensembles of hundreds to thousands of galaxies. It has been known for decades that when two clusters of galaxies merge, they can produce radio emission spanning millions of light years. This emission is thought to come from particles that are accelerated during the merger process. New research using LOFAR is beginning to show this emission at previously undetected levels from clusters of galaxies that are not merging. This means that there are phenomena other than merger events that can trigger particle accelerations over huge scales.

Caption: The galaxy cluster Abell 1314 is located in Ursa Major at at distance of approximately 460 million light years from earth. It hosts large-scale radio emission that was caused by its merger with another cluster. Non-thermal radio emission detected with the LOFAR telescope is shown in red and pink, and thermal X-ray emission detected with the Chandra telescope is shown in gray, overlaid on an optical image. Credit: Amanda Wilber/LOFAR Surveys Team/NASA/CXC

High-quality images

LOFAR produces enormous amounts of data. The equivalent of ten million DVDs of data has been processed to create the low-frequency radio sky map. The survey was made possible by a mathematical breakthrough in the way we understand interferometry.

A large international team has been working to efficiently transform the massive amounts of data into high-quality images. Pre-processing of the LOFAR data within the archives in the Netherlands, Germany and Poland reduces the size of the huge LOFAR datasets before the data are transported to member institutions for the images to be made.

Most of the images for the first data release were made on the University of Hertfordshire's high-performance computing facility, supported by Science and Technology Facilities Council (STFC) funding for LOFAR-UK. "Making these images in a completely automated way has required a lot of investment in software development as well as new computer hardware," explained Martin Hardcastle, University of Hertfordshire. "But the payoff is the unprecedented quality of the data, which will allow us to study the evolution of galaxies and their activity in more detail than ever before."

LOFAR

The LOFAR telescope is unique in its capabilities to map the sky in fine detail at metre wavelengths and is considered to be the world's leading telescope of its type. The European network of radio antennas spans seven countries and includes the UK station at STFC RAL Space's Chilbolton Observatory in Hampshire. The network is operated by ASTRON in The Netherlands.

Professor Chris Mutlow, Director of STFC RAL Space said: “UK scientists are at the heart of this international project to better comprehend our Universe. This new survey has already mapped thousands of galaxies, helping us understand how these galaxies and black holes evolve. The LOFAR-UK station at RAL Space's Chilbolton Observatory will be celebrating its 10th anniversary next year, so it is timely to see such fascinating results from this radio sky survey. This is something we are extremely proud to support."

The signals from all of the stations are combined to make the radio images. This effectively gives astronomers a much larger telescope than it is practical to build - and the bigger the telescope, the better the resolution. The first phase of the survey only processed data from the central stations located in the Netherlands, but UK astronomers are now re-processing the data with all of the international stations to provide resolution twenty times better. "We will be able to identify hidden black holes, study individual clouds of star formation in nearby galaxies, and understand what jets from black holes look like in the most distant galaxies," says Leah Morabito, University of Oxford. "This extra phase of the survey will be truly unique in the history of radio astronomy, and who knows what mysteries we'll uncover?"

The next step

A special issue of the scientific journal Astronomy & Astrophysics is dedicated to the first 26 research papers describing the survey and its first results. A quarter of the papers were led by UK scientists. The papers were completed with only the first two percent of the sky survey. “This sky map will be a wonderful scientific legacy for the future. It is a testimony to the designers of LOFAR that this telescope performs so well", says Carole Jackson, Director General of ASTRON.

The team aims to make sensitive high-resolution images of the whole northern sky, which will reveal 15 million radio sources in total. “Just imagine some of the discoveries we may make along the way. I certainly look forward to it", says Jackson.

More information:

Institutes publishing the results

| The Netherlands | ASTRON, the NOVA (Netherlands Research School for Astronomy) institutes at Leiden University, Groningen University, University of Amsterdam and Radboud University Nijmegen, SURFsara, SRON, Ampyx Power B.V, JIVE |

| United Kingdom | University of Hertfordshire, University of Edinburgh, Open University, University of Oxford, University of Southampton, University of Bristol, University of Manchester, STFC RALa Space, University of Portsmouth, University of Nottingham |

| Italy | National Institute for Astrophysics (INAF), University of Bologna |

| Germany | Hamburg University, Ruhr-University Bochumm, Karl Schwarzschild Observatory Tautenburg, European Southern Observatory, University of Bonn, Max Planck Institut für Extraterrestrische Physik, Bielefeld University |

| Poland | Jagiellonian University, Nicolaus Copernicus University Toruń |

| Ireland | University College Dublin |

| Australia | CSIRO |

| USA | Harvard University, Naval Research Laboratory, University of Massachusetts |

| India | Savitribai Phule Pune University |

| Canada | University of Montreal, University of Calgary, Queen's University |

| South Africa | University of Western Cape, Rhodes University, SKA South Africa |

| France | Observatoire de Paris PSL, Station de radioastronomie de Nançay, Université Côte d'Azur, Université de Strasbourg |

| Denmark | University of Copenhagen |

| Iceland | University of Iceland |

| Mexico | Universidad de Guanajuato |

| Sweden | Chalmers University |

| Uganda | Mbarara University of Science & Technology |

| Spain | Universidad de La Laguna |

LOFAR

The international LOFAR telescope (ILT) consists of a European network of radio antennas, connected by a high-speed fibre optic network spanning seven countries, including the UK station at the Chilbolton Observatory. LOFAR was designed, built and is now operated by ASTRON (Netherlands Institute for Radio Astronomy), with its core located in Exloo in the Netherlands. LOFAR works by combining the signals from more than 100,000 individual antenna dipoles, using powerful computers to process the radio signals as if it formed a 'dish' of 1900 kilometres diameter. LOFAR is unparalleled given its sensitivity and ability to image at high resolution (i.e. its ability to make highly detailed images).The UK contribution to LOFAR is funded by the Science and Technology Facilities Council (STFC), part of UK Research and Innovation (UKRI).

Further information about the survey can be found on the LOFAR Surveys team website.